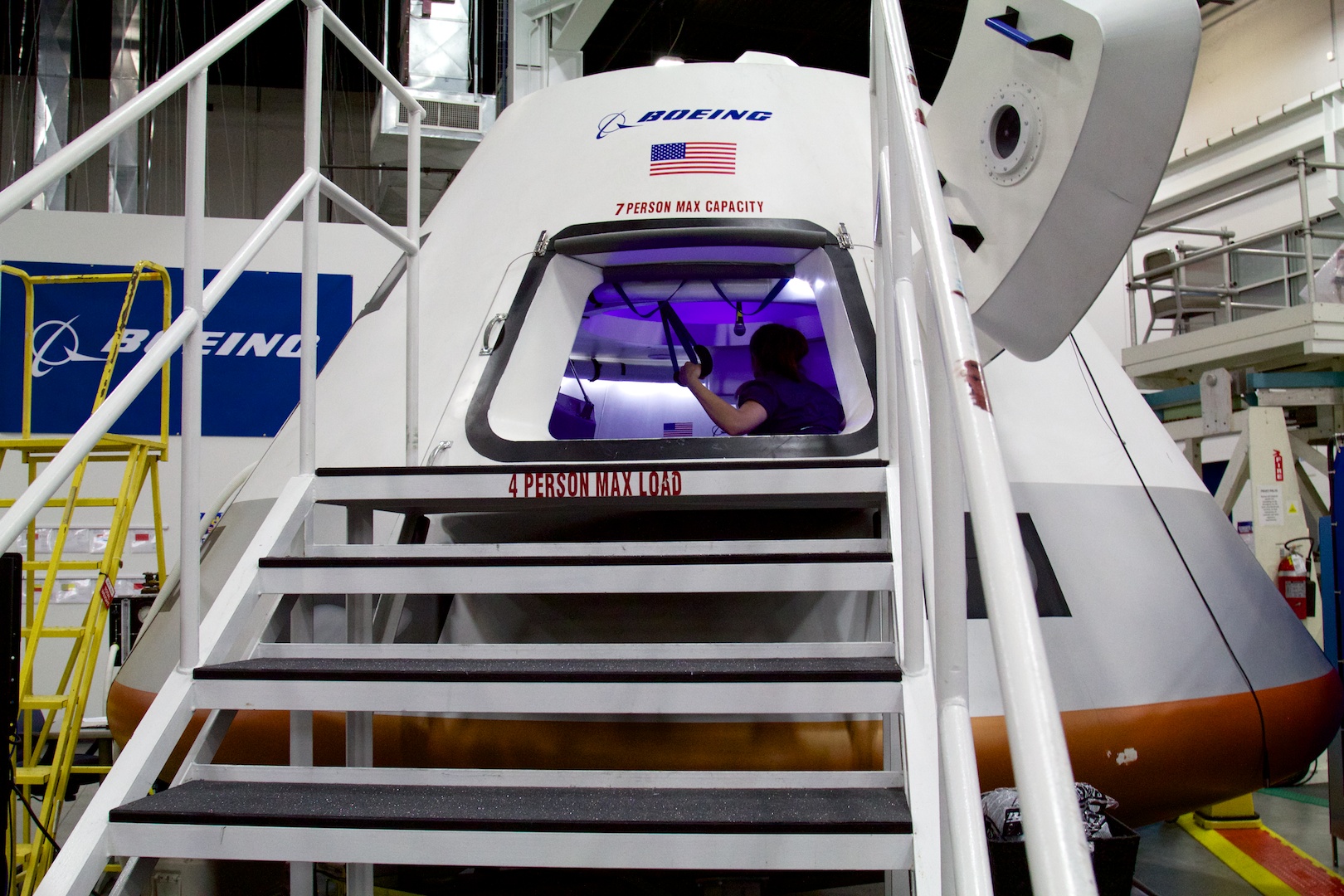

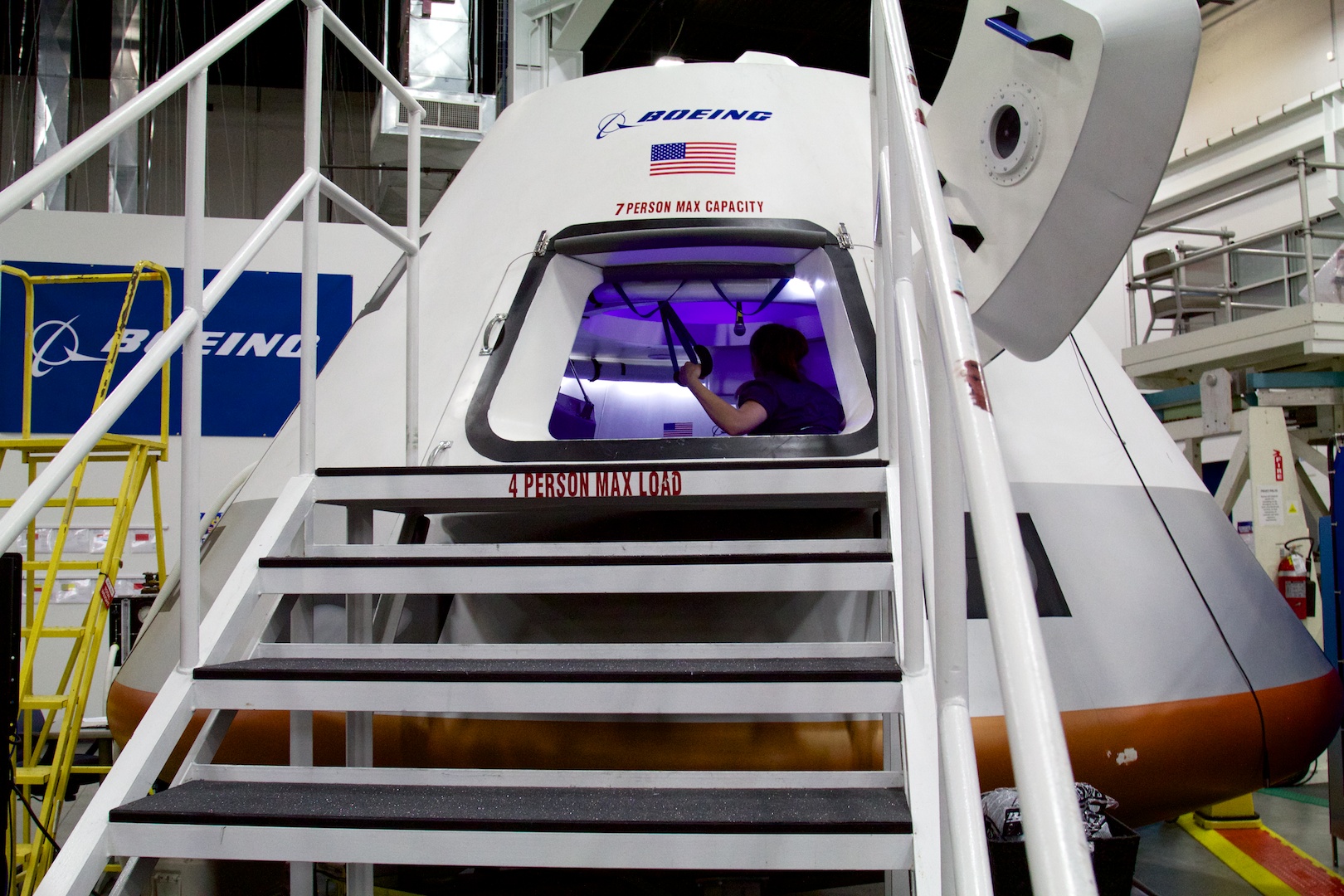

Reveal of the CST-100 commercial crew engineering test article.

Like Dragon it's upgradeable to beyond Earth orbit operations, but there's been talk Boeing is having trouble making it commercially competitive. This is why there're now talking of launching it on Falcon 9 v1.1 instead of the much more expensive Atlas V.

Like Dragon it's upgradeable to beyond Earth orbit operations, but there's been talk Boeing is having trouble making it commercially competitive. This is why there're now talking of launching it on Falcon 9 v1.1 instead of the much more expensive Atlas V.

Boeing took the curtain off its proposed commercial spacecraft this morning, allowing a limited number of press and media into one of its Houston facilities to crawl around inside a high-fidelity mockup. The spacecraft, designated the CST-100 (for "Crew Space Transportation"), is a large capsule, resembling a scaled-up version of the iconic Apollo command module.

>

>

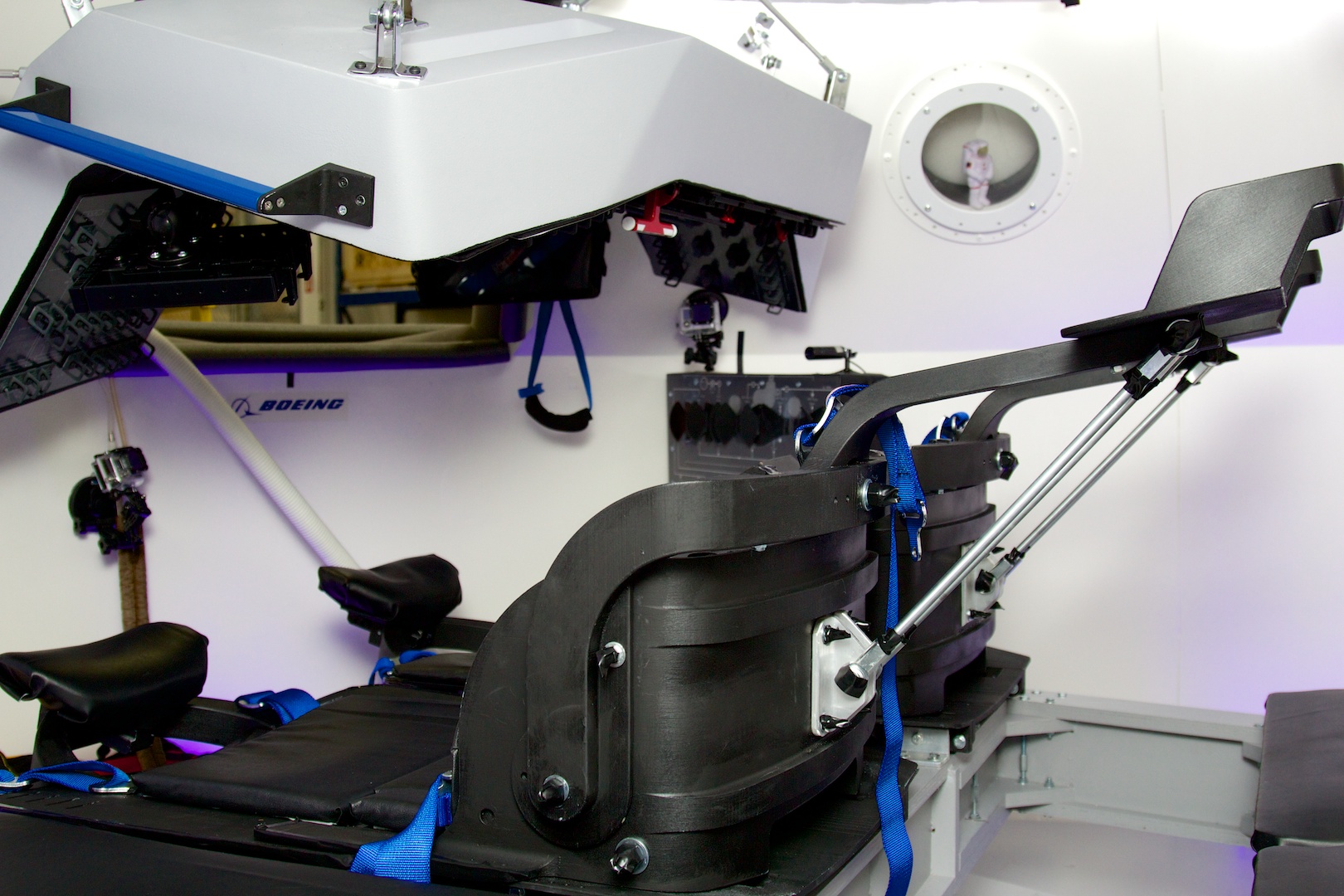

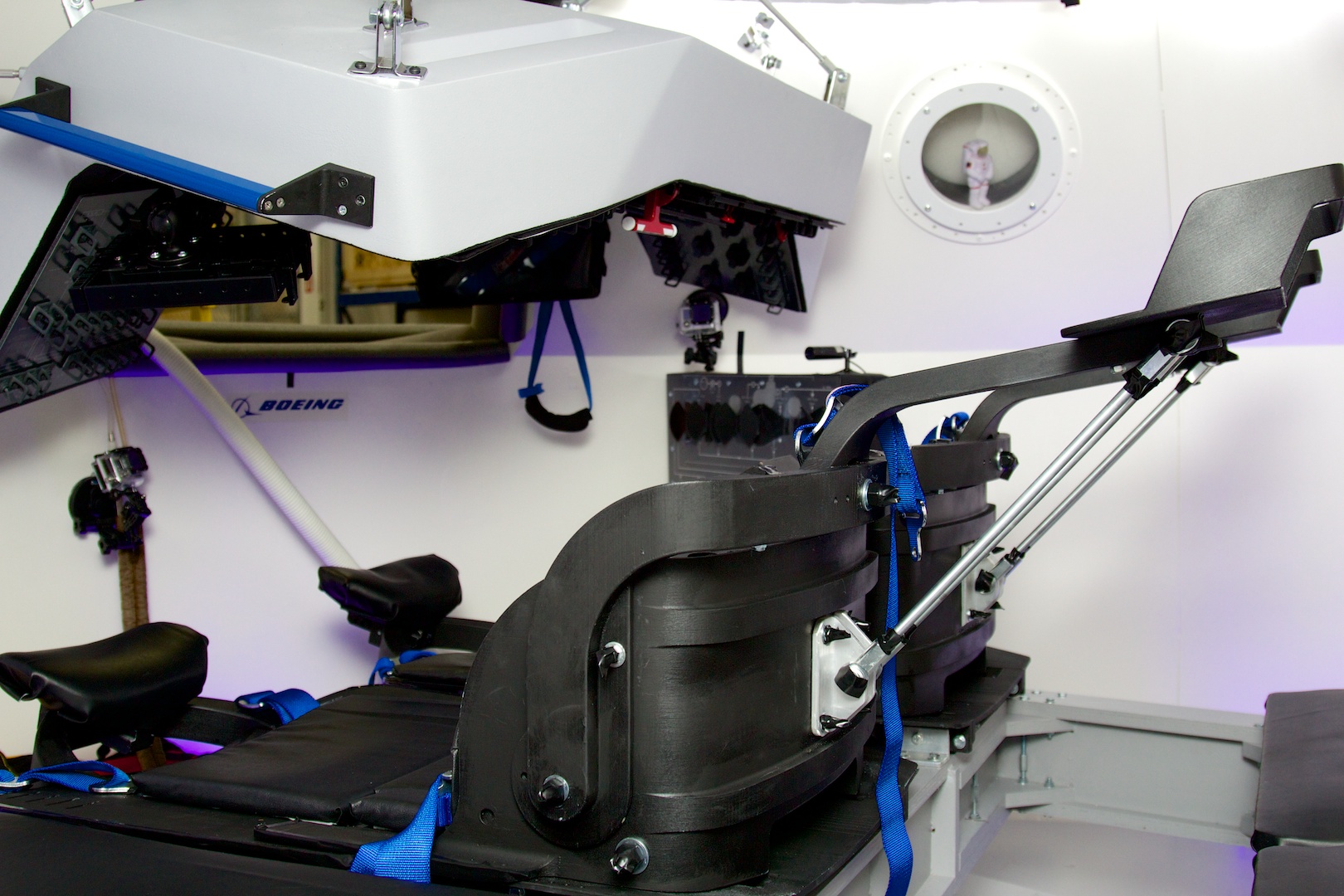

Cost savings is one of the largest driving forces behind the spacecraft's design—second only to safety. As much as possible, the CST-100 capsule uses "COTS" components (a popular aerospace acronym standing for "Commercial, Off-the-Shelf"), even in its avionics. Boeing Space Exploration vice president (and former astronaut) Chris Ferguson spoke in detail about the control consoles and instrumentation Boeing is planning on using for the CST-100. The plan is to equip astronauts with an "electronic flight bag," much in the same way that commercial airline pilots these days are being equipped with iPads and other consumer tablet hardware for all of their checklists and documentation.

Ferguson explained, in fact, that Boeing plans to use the same type of commercial touchscreen hardware—iPads, or Microsoft Surface tablets, or Android tablets—whichever company is willing to work with Boeing on the design. "If Apple comes to us and says 'Hey, we want you to use our product, and we're willing to do this and this and this,' well, hey, a tablet's a tablet, really!" he said. One of the big factors, though, is matching existing systems on the International Space Station and also upcoming flight systems in the Orion MPCV. Boeing wants there to be as much commonality as possible, so crews will be able to switch between spacecraft and space station without needing huge amounts of additional training. But as far as looking like previous spacecraft, like the space shuttle, CST-100 will be very, very different.

"All the hardware switches you see in there are backup and are never intended to be used normally," Ferguson went on. The cockpit contains hardware switches for all critical systems—opening and closing valves, for example—but the intent is for the crew to be able to fly the spacecraft and do all of its operating tasks through touchscreens. Or to not have the crew do those tasks at all—CST-100 is being designed with the capability to operate totally autonomously, unlike the space shuttle. The latter lacked the ability to be fully operated remotely (though that capability was added in 2006 with the addition of a special cable).

I asked Ferguson about the practicality of operating touchscreens in gloves, since the crew would likely spend their launches and landings in the same orange ACES suits being used by Serena Auñón. He replied that Boeing is investigating including a capacitive mesh layer in the fingers of the suits, sort of along the same lines as the "iPad gloves" folks in northern climates can buy to keep their fingers warm while they poke at their gadgets (though, obviously, much more air-tight and spacesuit-y).

Getting there and back

Boeing plans to have the CST-100 hitch its initial rides into orbit on the Atlas V rocket, coupled with a Centaur upper stage. The combination has an excellent safety record, and Boeing (with assistance from its United Launch Alliance joint venture) will be taking the extra steps necessary to "man-rate" the rocket—that is, prove by NASA's stringent guidelines that the rocket is safe enough to carry humans, rather than the cargo it's currently used for.

Atlas V isn't the only rocket with which CST-100 will be compatible; Boeing is designing the capsule to work with a wide variety of launch systems, including rival SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket. It's even possible that the CST-100 could be lofted by NASA's ultra-heavy-lift Space Launch System when or if it becomes available, though using that large a rocket to lift the CST-100 capsule would be overkill.

>

>

>

>

Cost savings is one of the largest driving forces behind the spacecraft's design—second only to safety. As much as possible, the CST-100 capsule uses "COTS" components (a popular aerospace acronym standing for "Commercial, Off-the-Shelf"), even in its avionics. Boeing Space Exploration vice president (and former astronaut) Chris Ferguson spoke in detail about the control consoles and instrumentation Boeing is planning on using for the CST-100. The plan is to equip astronauts with an "electronic flight bag," much in the same way that commercial airline pilots these days are being equipped with iPads and other consumer tablet hardware for all of their checklists and documentation.

Ferguson explained, in fact, that Boeing plans to use the same type of commercial touchscreen hardware—iPads, or Microsoft Surface tablets, or Android tablets—whichever company is willing to work with Boeing on the design. "If Apple comes to us and says 'Hey, we want you to use our product, and we're willing to do this and this and this,' well, hey, a tablet's a tablet, really!" he said. One of the big factors, though, is matching existing systems on the International Space Station and also upcoming flight systems in the Orion MPCV. Boeing wants there to be as much commonality as possible, so crews will be able to switch between spacecraft and space station without needing huge amounts of additional training. But as far as looking like previous spacecraft, like the space shuttle, CST-100 will be very, very different.

"All the hardware switches you see in there are backup and are never intended to be used normally," Ferguson went on. The cockpit contains hardware switches for all critical systems—opening and closing valves, for example—but the intent is for the crew to be able to fly the spacecraft and do all of its operating tasks through touchscreens. Or to not have the crew do those tasks at all—CST-100 is being designed with the capability to operate totally autonomously, unlike the space shuttle. The latter lacked the ability to be fully operated remotely (though that capability was added in 2006 with the addition of a special cable).

I asked Ferguson about the practicality of operating touchscreens in gloves, since the crew would likely spend their launches and landings in the same orange ACES suits being used by Serena Auñón. He replied that Boeing is investigating including a capacitive mesh layer in the fingers of the suits, sort of along the same lines as the "iPad gloves" folks in northern climates can buy to keep their fingers warm while they poke at their gadgets (though, obviously, much more air-tight and spacesuit-y).

Getting there and back

Boeing plans to have the CST-100 hitch its initial rides into orbit on the Atlas V rocket, coupled with a Centaur upper stage. The combination has an excellent safety record, and Boeing (with assistance from its United Launch Alliance joint venture) will be taking the extra steps necessary to "man-rate" the rocket—that is, prove by NASA's stringent guidelines that the rocket is safe enough to carry humans, rather than the cargo it's currently used for.

Atlas V isn't the only rocket with which CST-100 will be compatible; Boeing is designing the capsule to work with a wide variety of launch systems, including rival SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket. It's even possible that the CST-100 could be lofted by NASA's ultra-heavy-lift Space Launch System when or if it becomes available, though using that large a rocket to lift the CST-100 capsule would be overkill.

>

>

Comment